Dudamel and a Ricardo Lorenz world premiere; Yunchan Lim and Schumann’s piano concerto; and Kate Blanchett performing in Beethoven’s Egmont, at LA Phil

By S.E. Barcus

February 12, 2026

“People of the Netherlands!

Trust in your own strength.

Stand fast, and the day of liberation will dawn!”

— Egmont

We sit and get comfy within the warm, wood-paneled, ear-shaped, curvy Cathedral of Gehry’s Disney Concert Hall, with its own sort of Rose-window centerpiece — the jutting, angular, Superman’s-Arctic-crystal-shard-castle of magnificent organ pipes.

And for what? Why are we here tonight? Well … allow me to re-iterate the subtitle, above: Gustavo Dudamel in his last season (literally passing the baton) with LA Phil, conducting a Ricardo Lorenz world premiere; followed by hot pianist Yunchan Lim performing Schumann’s piano concerto; and Tar — er, Kate Blanchett — performing as Goethe’s and Beethoven’s Narrator in Egmont’s incidental music, all with the fabulous LA Phil. (Holy mackerel, man, we would’ve bought the ticket for just one of these pieces! Save something for the rest of America, fer Pete’s sakes!)

Venezuela (Humboldt’s Nature)

The Ricardo Lorenz world premiere, “Humboldt’s Nature,” is a symphonic fantasy for nearly ONE HUNDRED musicians, (geez Louise!), and utilizes almost every percussive instrument one can imagine. Based on the German scientist Alexander von Humboldt’s travels through Latin America, the opening movement heralds our entry into 18th century Venezuela with a recurring 5 beats of loud bells, between quiet mysterious but crescendoing strings. Then quiet again, and a piano theme, the first we hear of this recurrent, Berlioz-styled “idée fixe,” representing Humboldt and a colonial/European sensibility.

The piece carries on, bouncy, rhythmic, exploratory — ah! watch out for those flies and bees (played by bursts of buzzing strings)! — as we march onward and gradually transform once again into thick, luscious strings, going through this “Transfiguration in New Andalusia 1799,” the title of the first movement, and the moment of Humboldt’s enlightenment toward Nature and humanity’s place within it.

There are complicated rhythms, hard to peg. Here’s an obvious six-count, there, then it’s gone, stops and starts, constantly changing — but also with a constant “pulse,” and with overall pleasantly “accessible” tonal music, making wonderful use of xylophones and bells, nicely muted trumpets, those “fidgety woodwinds” — all, overall, creating a feeling of awe for Nature — like something Copland might have written for this half of the Americas. Then piano and xylophones and bass strings once again. (The bass strings are placed around the piano up-stage right, not down-left like most symphonies, which is interesting.)

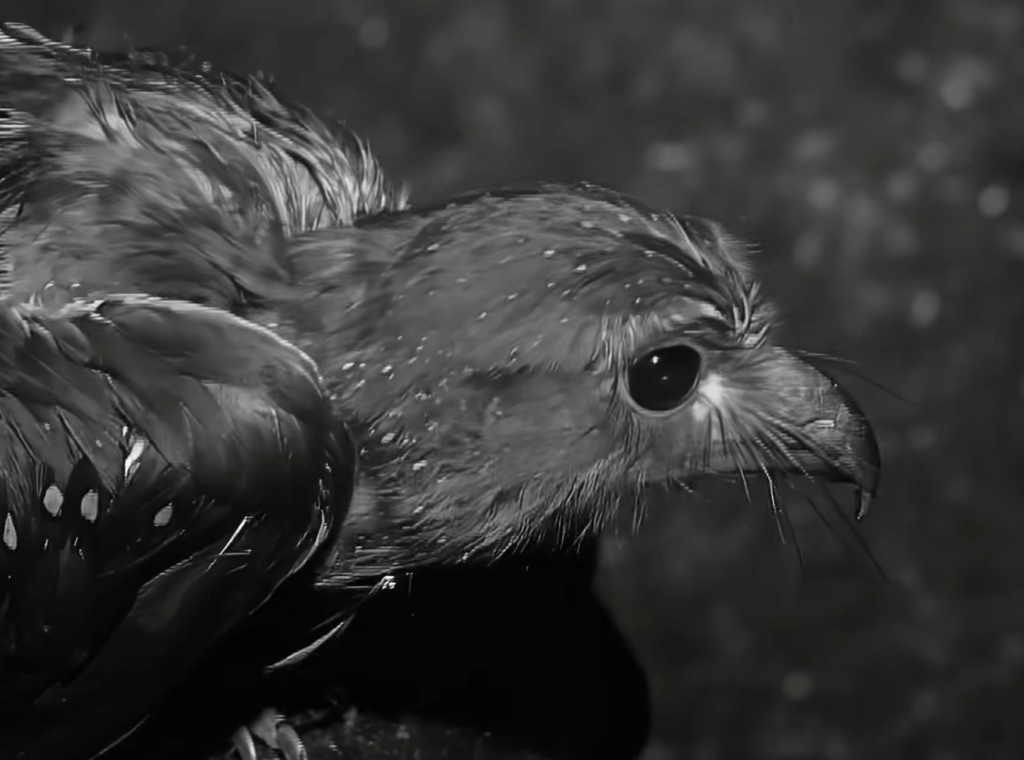

The next movement, “Steatornis Caripensis,” is named after the scientific classification of the nocturnal Guacharo bird, classified by Humboldt himself, and very culturally (and personally) significant to Venezuela and Lorenz. It starts with menacing tambourines that must have been rattle snakes, the way they are played, as we enter the bird’s cave at night? At one point a clicking percussion that might have been the echo-location of this bird? Then punctuated rhythmic moments, backed by drums, in twos, threes, fours….. with a seven-count repeating ostinato, then a faster tempo of three beats making your heart want to leap out of its chest. Taken over by horns here, xylophone there, while strings interweave around them during the journey, all punctuated with various drums. (To get a sense of the percussive variability of this piece, we are, at one time or another, struck by: crotales, triangle, guiro, vibraslap, Chinese gong, multitudes of various symbols and drums, slapstick, ratchet, cabasa, bamboo rod, marimba, timpani, congas — just to name a few! … When you get commissioned to do a piece by LA Phil — you lay it ALL out there, brother!) Ends with a final hissing tambourine snake at the end….

Despite an incessant triplet, cross-sticking the side of a drum, the next movement has a lovely, calm wind instrument that starts us off with what seems like a nod to Debussy’s fawn? “Venus of Tacarigua,” named for a lake and its peoples (and their buxom’ed figurines) that Humboldt comes across — renamed Lake Valencia by colonists — but renamed once again, and reclaimed by Lorenz. The other instruments quickly join in, things get lively and raucous once again, with that constant rhythmic pulse, the vibrant drumming of the culture that lived there. Until it stops, and builds up again. Ending suddenly with very rapid plucking of strings, impressively done by the LA Phil string players, sounding like a warm bubbling hot spring. Finally, a loud SNAP ending — perhaps the wake-up call? The warning of the climate change that agriculture was causing this lake, as first described by Humboldt, at the dawn of climate science.

The “Sailing on air” movement then comes in nice and slow with piano and flute, with wind blowing, water flowing, made by the sands rolling around an ocean drum. (Oh yeah, there’s also an ocean drum….) This gentleness gives way to a sweet keyboard percussion, and rising winds and strings. Nice “bending” of the note, by everyone, suddenly, possibly turning around a bend on the Orinoco River that Humboldt canoed down, looking for the Amazon River. All while he looks to the sky, taking climate science measurements. This is a dreamy piece. A peace. Probably the real moment of Humboldt’s existential transcendentalism. As smooth and creamy as … well, as a yummy Humboldt fog cheese. (And yes, so-named for Humboldt County, California; and yes, so-named for this cool pioneering German environmentalist.)

But the dream suddenly ends — interrupted by sudden civilization-like noises. Activity, hustle-and-bustle that’s a little “American in Paris”-feeling. We’re in Cuba now, on the way home to Berlin presumably, and Humboldt sees — and is disgusted by — the institution of slavery, by its inhumanity and injustice. He becomes an abolitionist.

We get it. It is hard not be repulsed, and dedicate yourself against inhumanity and injustice, when you see things like — like … I don’t know … like seeing innocent Venezuelan fisherman being murdered by the United States military, as they cling to their ship, begging for help. (I went tonight after attending LA’s amazing “Monuments” exhibits, btw, which I highly recommend, and which thematically complimented tonight’s program in many ways .)

The entire work ended with trumpeting fanfare, followed by the trickling piano return of the idée fixe, as Humboldt tries to reconcile all he has experienced, as dreamt by Lorenz’ fantasia. Finally, the auditorium is overtaken by recorded audio, for its last sounds. Increasingly loud natural noises of insects and birds. Even the human musicians must be quiet now. We all must be quiet and listen, in our cave, to the sounds of actual non-human music (if mediated).

There it is— an historical fantasia of humanism, of environmentalism, politically charged with modern day Venezuela in the background, all composed by a master contemporary composer of rhythm, with a wonderfully varied intertwining of musical ideas and moods. What a wonderful, meaningful work of art for this perilous time we are living in right now. Thank you so much, Ricardo Lorenz!

And you, as well, Venezuelan maestro-colleague, Dudamel — who does not conduct with any exaggerated flamboyance. He’ll give a slightly bigger arm gesture here and facial expression there, at pointed changes, when it matters, like in the final movement of “Humboldt,” when there were constant rhythmic changes, he’d go back-and-forth in rhythm but with a sudden jolting re-start, off beat, like a dancing doll with a hiccup. But otherwise Dudamel is all confident and precise and keeps it as together as his philharmonic. A great, invisible, and mostly modest conductor, giving the applause and spotlight to his musicians at every turn throughout the night. He is all business, and a true professional. “Just the facts, ma’am, just the facts”, as they might say in Dragnet (whose police tower is just down the street!).

Fidelio (Lim’s Schumann)

Yes, there was more than just a world premiere! 21-year-old Yunchan Lim — taking K-pop to the K-lassical — is one hot commodity right now.

Schumann’s only piano concerto, in A minor, is such a romantic creature of the 19th century, and so obviously inspired by rhythmic and harmonic tricks of the Beethoven-trade. The first movement of this concerto famously steals a theme from Beethoven’s opera, Fidelio. And the main theme of Fidelio, don’t forget, is the triumph of love and personal sacrifice over political tyranny and injustice. Hmm…. That’s interesting for tonight….

Lim plays this beautiful (if at times schmaltzy) Schumann piece as melodramatically as anyone from the Romantic-era, full of swooning over a love interest. He literally sways back and forth while he plays, just as much as this swooning music. Even Dudamel has a little hip sway going on with this movement. When things get forte, Lim hits hard enough, and when throwing back to the symphony, he’ll give an extra exaggerated toss of his sensuous thick long black hair. The flailing reminded me of cartoons of Liszt playing the piano.

For the most part, Lim is so in control and tight with the orchestra that he needs little-to-no conducting. Dudamel just gives the occasional dip of his left hand for Lim to see where the rhythm is. The best, sweetest moment between these two artists occurred when they weren’t actually playing music — but instead between the 1st and 2nd movements. The 1st movement ends so passionately, with all of those trills, that Lim has to take a moment to brush back his sweaty lush hair a few times. Dudamel looks, waits, looks, waits. Gives an expression of, “ok, u done? We ready to move on to the 2nd movement?” This exchange was picked up by the whole audience, quietly giggling. And don’t get me wrong. Lim wasn’t being a prima Donna or anything. And Dudamel wasn’t being condescending or overly stern. It was just … cute. Kind of fatherly, given Lim’s young age. You had to be there, I guess. (Lim might wanna cut his hair a little, though, lol.)

The second movement is sweet and delicate, and Lim expresses it so gently that you want to go out right there and hear his Chopin recordings. The whole work is played so wonderfully by both Lim and the Phil. And for its final movement, we do get very difficult rapid dyads crashing rapidly downward, performed flawlessly by this very talented young virtuoso. The end of the last movement, with his rollicking arpeggios and final crashing chords, perfectly timed with a grand flippy-flip of the hair, brought immediate applause and standing ovations.

For an encore, to go along nicely with our A minor concerto, our cool kid from Korea continues in A minor, this time Chopin’s Waltz in that key — reminding us again to maybe go out and purchase his Chopin recording (or maybe his recording of Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes — if you’d perhaps like to compliment tonight’s Humboldt “transfiguration”?). Lim plays this sweet little waltz without any of the aforementioned showmanship. It is delicately performed, quiet and contemplative, revealing a gentleness. Almost embarrassed by such emotion(?), Lim very quickly bows at the end and runs off stage, before we can even stand up again for another ovation.

Minneapolis (Blanchett’s Egmont)

Then comes actress, Cate Blanchett, and her bona fide classical music cred, given her star performance in Tar, and her proclaimed love of our best classical music writer alive today, Alex Ross, in interviews she’s given. She generously lends her star power to focus us on Beethoven’s incidental music from Goethe’s play about an old Flemish hero, Egmont. A Ludwig work that is not as commonly performed, but that is the right work — like it was for the Hungarian 1956 revolution against Soviet tyranny — for our time, right now.

If Schumann was an echo of the master, for me, the powerful Egmont overture was — once again — a reminder of why many consider Beethoven perhaps the greatest composer who has ever lived. Expert use of the various parts of the symphony, instantly emotionally wrenching. I don’t think any music can stimulate norepinephrine OR opioid receptors as strongly as Beethoven’s.

Then, at the end of the overture, the lights black out and Blanchett — who has been politely sitting behind the musicians so as to not upstage them — stands immediately erect, alone, spot-lit, and unleashes her narration, not bland from a book, but acted — with lines memorized and delivered with all the power and majesty she brought to Queen Elizabeth or Galadriel. She didn’t have to give us a true acting performance, but this is one of the world’s greatest actresses we’re talking about. Blanchett is not calling this in — who u think she is, anyway? Throughout the work, she will move about the auditorium with clever dramtic blocking, at times sitting out in front of the musicians here, in the middle of the work, with that castle-like-organ now pointedly lit like a theatrical set piece, giving us the feeling of a royal castle in Brussels.

After the first narration, our soprano, Elena Villalón, gives one of her two lovely songs that, for me, rival any of the more-popular Lieder of Schubert.

The adaptation by Jeremy O. Harris not only gives us nice agit-prop, tonight, but also some decent puns. What do you do if you find yourself in such a time as the Netherlands during Spanish oppression (or in such a time as ours)? Nothing? Don’t do it, implores Egmont. “Predators are praying for your complacency. … Then preying … on you.” Some of the adaptation is straight-up out of today — “There are battalions gathering. On the banks of Brussels, on the banks of Portland, on the banks of Tehran, on the banks of Minneapolis — battalions pointing their guns at citizens with charges of heresy and treason. … And Egmont, the Inquisition on his doorstep.” (I do wonder why Harris didn’t include L.A.? We’re in L.A. tonight, and while the citizens of Minneapolis get my vote for Nobel Peace Prize, the citizens of L.A. were pretty damn inspiring, too, when they took the opening salvo of the federalized National Guard — and held their own. So much inspiring music to go along with so many frightening but also inspiring moments in America over the past year.)

And in case you still missed the point — “Egmont went to the Cardinal and took an audience with the King. Yet the Inquisition raged on. … He trusted the word of the King … yet quickly he was taken away by the guards. “Fucking bitch!” A path to the dungeon, death awaits him. “Fucking bitch.” “That’s fine, dude, I’m not mad at you.”” This was rightfully heart-wrenching and disturbing.

For her final narration, Blanchett is actually up over all of us, next to that beautiful organ, giving Egmont’s final, famous narration to fight! Wake up! They are coming for you, in Brussels, in the Netherlands, in Portland, in Minneapolis! All while some of the best music by Beethoven in his late Middle/heroic period swells up. (Fight Napoleon! Fight your own chance-misfortunes of deafness and unrequited love!) While she implores us, a marching snare drum grows louder and louder, just outside an open side door of the symphony, menacing. Then the pause representing Egmont’s execution and martyrdom, followed by the roaring “Victory Symphony” of Beethoven, complete with Blanchett unleashing a completely uninhibited dance of freedom in all white, that recalls, for me, Emma Goldman’s famous line: “if I can’t dance, I don’t want to be a part of your revolution,” focusing on WHY we fight. For freedom and our loves.

So. Venezuela, Fidelio, and Minneapolis walk into a bar. Bartender asks, “what do you want?” They answer, in unison, “Freedom and Justice.”

Yeah, sorry, it’s not a funny joke. …. Cuz absolutely nothing is funny lately.

At LA Phil, Thursday night, though, we at least got some Beauty, if for a night.

Copyright February 12, 2026

S.E. Barcus is also on Facebook.

Leave a comment