Vienna Koncerthaus, Mozart Hall

S.E. Barcus, January 17, 2026

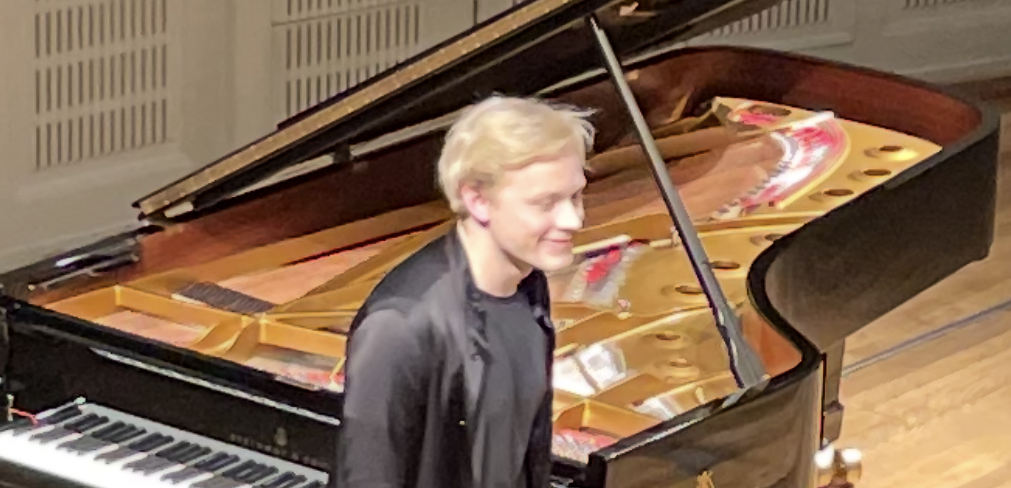

Wowza. What a Wizkid. Alexander Malofeev bounded into Vienna Saturday night, January 17, and did not disappoint.

There we were, waiting in the Koncerthaus, in the church-like Mozart Hall. Suddenly the side door opened, and the stark-white, golden-haired fellow with the happy-boy face, dressed in his sleek-black shirt, leaped onto the stage. He briefly acknowledged the polite applause, sat down — and just as ‘attacca subito’ as he was with the first two works that night — he immediately went to town.

Nordic Works

The first half of the night highlighted Nordic composers Sibelius, Grieg, and Rautavaara. Sibelius’ Five Pieces Op. 75 was up first — known as “The Trees”, for the impressionistic and metaphorical look into five different Finnish trees for which each piece is named. The first, “The Rowan Blossoms,” started us off with a melancholia, a piece one could easily peg came from the Romantic period, whether you’d heard it before or not. It also introduced us to Malofeev’s “ready position” – legs together, elbows at sides, with forearms poking straight out to the keys like little Tyrannosaurs Rex arms.

To go along with the “gold” theme, he was a little reminiscent of Glenn Go(u)ld, given how low his chair was, such that his thighs were jutting upward, giving the impression of a man scrunched into a toy piano. And, ok, one last “boyish” feature — (sorry, Alexander, gotta calls it likes I sees it! 🙂 ) — his hands, early on, seem huge and disproportionate to his body, similar to his contemporary, Lisiecki’s hands. Like a puppy dog flopping around with huge paws they have yet to grow into. By 24 years old, Malofeev seems perfectly genetically made for piano playing, brother to the 12-fingered pianist oddity from Gattaca, or something.

But enough of appearance. His “blossoms” were quite delicate, and right away disclosed a gentle maturity that was hiding beneath his otherwise seemingly ADHD-fun demeanor. Then, for secondsies — with its Grave tempo marking – was our second tree, “The Solitary Pine,” sounding undeniably as sturdy and resilient as the tree itself, but also symbolic of Finnish nationalism, as it was described, when it was first performed, as steadfast against “the icy wind from the east.” Hmm…. One wonders, in Finland, whatever that could have POSSIBLY referred to? (And whatever could it still refer to?) For Malofeev, a Muscovite (now living in Berlin, being against the Ukraine war, himself) to play this piece was, for me, symbolic — in and of itself — of a solidarity. A solidarity against Russian revanchist wars and senseless killings. A solidarity with Finland, just recently in 2023 a member of NATO. (And much more solidarity for NATO than we Americans are currently showing, with “our” horridly gangster-like behavior toward Greenland.)

Then, “The Aspen,” which after the Pine, feels like spring is around the corner, but not quite there. A quiet light just starting to peak out. Hesitant, with its quiet double-chords, and intermittent harmonies that remind me, anyway, of Janáček. And then, finally, full-on nice weather and happiness with “The Birch,” which conjures images of dancing around a May pole. A waltz then “finn-ishes” the work, appropriate for Vienna. It’s, “The Spruce,” evoking Finnish forests that span far into the landscape/soundscape, with wind-blown trees of rolling arpeggios, separated by slow, yearning lyrical sections. The emotional impact of this famous piece – and Malofeev’s wunderbar rendition — could easily be used for a Hollywood film score.

Then to the Grieg, a whole new composer and work – not that one would know it if one did not know tonight’s works. Because Malofeev proceeded into the first movement with just as immediate an attack as he did between all of the pieces within “The Trees,” as if the two works were one. These attacks were interesting in another aspect: Malofeev often held the last notes of these pieces with the sustain pedal, not the fingers, very gradually releasing the pedal, until — JUST as there was the hint of a scratchy twang of strings, like electric guitar feedback or something — he would release completely and attacca subito into the next piece or movement. Very punk rock piano.

He embodied and brought out the dancing quality of the Grieg’s Holberg Suite Op. 40 for piano, at times almost dancing himself. While he might have started the night compact and perhaps too close to the keys, in that dainty “ready position,” when the pieces call for it, this guy Malofeev backs away from the piano, with an easily-6-foot bird-of-prey wingspan, often looking away from the piano, head tilted up, either toward us or toward the back wall, eyes closed, obviously listening into the piano closely with his ears. And when a difficult passage called for it, he could twist and turn his body like some circus contortionist to get just the right strike of the notes, at times one elbow up, while the other is over there, like he’s in a Picasso painting. Some of Grieg’s movements have such definitive endings (and remember that he did not stop for applause after the Sibelius work), that when Malofeev savored the silence for a long while after the Gavotte, one person in the audience started clapping. This was met with Malofeev playfully scolding them with a “no-no, not yet” gesture of the head, and then he proceeded into the Air. So! As “boyish” as he might seem, now we know — this guy’s in command of the night, not us. Don’t peeve the Malofeev!

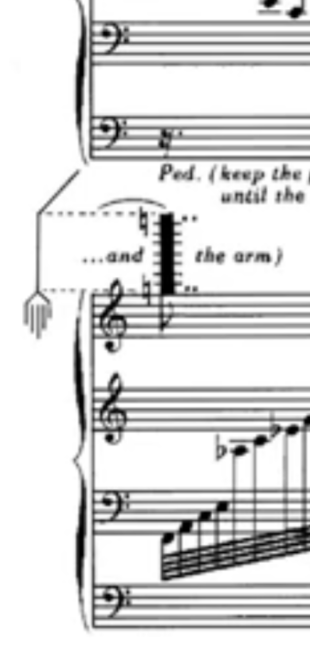

To close out the first half, the Finnish composer, Rautavaara, and his “Fire Sermon,” which was without question the craziest, most fun experience of the night. (Thank you for a smidgeon of contemporary classical music, Malofeev! – TRUE “modernity,” as opposed to that frozonym term — that period of time we still call “Modern”.) “The Fire Sermon” is exactly as hot and fiery as the title suggests. Early on, hands fly to the upper register in blistering madness, and Malofeev himself looks almost demonic at the notes as if they are somehow against him. The first movement also brings us a moment of calm smoke in the distance, as Rautavaara directs to never let up the lower notes, so that the strings will continue to resonate faintly and mysteriously, as an “echo,” while the higher notes go on playing.

Tone clusters abound, slapping keys in between the inferno, and not in a gimmicky way (like, to me, Henry Cowell, who explored this compositional technique, can sometimes sound), no, these tone-clusters and palmed moments expressed the random loud crashings down of a building’s walls from a fire, perfectly and artistically, combined with Malofeev’s twisted torso and — oh shit! he slipped and accidentally crashed his entire forearm onto the high notes! …

Oh. No. No, he meant to do that, sorry. It was written in, by this contemporary master composer.

And what his poor fingers have to do, here?! In the third movement, they are all twisted and crooked as they speed rapidly down a descending passage of thirds, in and out of the black keys like an obstacle course, running madly through a slew of rubber tires.

What an amazing, crazy piece of music! We have so many water impressions in the piano literature – finally some good red-yellow-and-gold FIRE. For that element, this piece is up there, for me, with Jennifer Higdon’s “Fiery Red” in her Piano Trio. So — ok, ok – by the end of this “First Act,” he’d won the crowd over and the polite applause morphed into mayhem, as we had to concede – this was one sehr gut und skilled piano virtuoso.

Russian Works

The second half featured all Russians, as if it takes a Russian to know a Russian? Similar, again, to the Polish-Canadian Lisiecki, and how he used to play mostly Chopin. I’m not sure how much this ethnicity thing is marketing, and how much is Malofeev really WANTING to play Russian music. For example, I don’t think an American is the “best person” to play Gershwin. Isn’t music a perplexing “meaningless” abstraction? An international language, and all that? All pianists on Earth are raised on Bach — can only Germans really “get him”? Or is it “cultural appropriation” to assume that we can? Etc, etc. The whole thing – as a humanist – just seems like marketing, to cynical ol’ me.

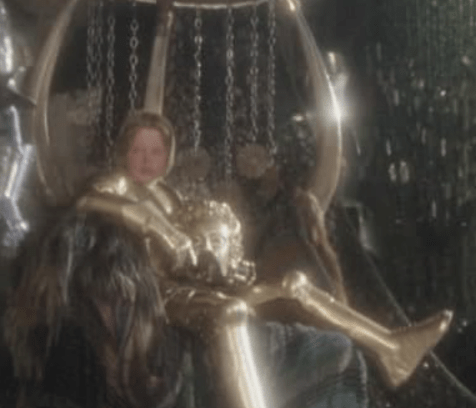

Anyway, out Malofeev bounded, once again, golden-haired, but now with a slightly playful sinister glimmer in his half-closed eyes, basking in our more enthusiastic applause. Like the Golden Boy Mordred from the old Excalibur film. As if to say, “NOW you understand my greatness, and are slaves to my whims!”

(And, yeah, I mean the term, “boy,” sorry — absolutely no offense intended. I use a 21st century definition of childhood, not that of the dark ages, where we wanted kids to have kids right at puberty … since we croaked by 40. Today? Childhood, in a highly civilized world, goes to about 26, when the development and maturation of prefrontal cortex is completed. Which is why you can stay on Obamacare to 26!)

Prokofiev’s Sonata No. 2 in D minor was just fabulous. An amazing piece, played with a virtuosity that had complete control of his audience. The piece is so crisp and clear and at times dissonant and fun and odd and … Prokofiev. The final Vivace movement of this piece roars out of the piano like a bull, and features many fast runs, only to roar back into the piano at the end — like we captured the bull (“Shut the gate! Close the lid!”) — with Malofeev nearly falling off his low-lying chair to the left with the last loud descending run into the lower register, leaving no doubt that the piece was over, and yanking from us an immediate ovation. No NBA or soccer player could flop as well as that! For myself, I do, personally, love a good performance. Not just the music – but the whole shebang. Like Yuja Wang, Malofeev performs like a rock star who knows just how and when to deliver the pizazz that you went and got all gussied up for.

Then the Scriabin, and – again, appropriate for Vienna – a Waltz. In A-flat Major. Not that it is an obvious “ONE-two-three, ONE-two-three” kinda waltz, given its four-beats and five-beats riding over top in the right hand. And not nearly as “mystical” as some other Scriabin works, overall. Actually quite lovely, with only random hints of dancers and poofy dresses popping in and out at times. More of a pastiche of a waltz than a waltz. And perhaps the most pleasant Scriabin I have ever heard. Why, I did not have the impression that the music was going to bring about the end of the world, not even once! (Malofeev seems to have his head on his shoulders. When he was interviewed in the past, he admitted that Scriabin fans were “a little cultish.” Hear, hear, brother.)

Stravinsky’s “Symphony for wind instruments” was next (with piano transcription by fellow Russian, Arthur Lourié). The opening is like a fanfare. One can really hear the crispness of wind instruments. But by the end, there is a slow, quietness, with a final chord held by Malofeev, no sustain pedal this time, hands on keys, for probably a full half minute. Then right into Arthur Lourié’s pieces to complete the program. (Were we supposed to clap for Stravinsky? Was he waiting for us to clap? …. I sure as hell wasn’t going to get scolded!)

The Lourié pieces – his “Five Pieces” (although jumbled in order this night) were a bit slow and quiet for much of it. Malofeev ends with pieces #2 and then #1, which was a nice choice, since the end of #2 sounds like the beginning of #1, and thus made for one longer piece. The end of #1 is quiet, and he holds those last notes down, once again hands on the keys, listening for the silence for what seemed an eternity. (Did Cage’s 4’33” somehow sneak into the program?) Until finally, only after all of the strings had stopped vibrating and all of the sound waves had stopped ricocheting off of any wall in that Hall … THEN, he was done. Then we were allowed to clap. This was a moving moment, almost commanding us to have an awe-inspiring (or for some, “religious”) experience in that silence. But it also meant that all of the fun energy we had been having, with the Prokofiev sonata and Rautavaara’s fire, had now long faded away. And we had been nearly lulled to sleep.

This was put right with the Rachmaninov encore (Opus 3 No 2), followed by our only German tonight, with a dainty Handel piece (Minuet in G minor), played completely in that prim and proper “ready position” once again.

Final encores – Prokofiev’s Toccata and Glinka’s Mazurka — were a good way to end a night. And perhaps a gauntlet thrown to Yuja Wang, who frequently ends with the Toccata, herself?

Overall, watch out for this fellow Malofeev. He’s quite good, and it is slightly scary that he is not satisfied with “just” the piano. In that recent interview, mentioned above, he revealed that he thinks symphonies are better (!) than piano because they are “bigger.” Do I see a future where Malofeev is the next big conductor-pianist, like his fellow countryman, Vladimir Ashkenazy…? Who knows?! Que Será, Será. For us in Vienna that golden Saturday night, though, we were more than happily satisfied by these “mere piano pieces,” played by the fantastic Golden Boy from Russia.

Copyright January 18, 2026

S.E. Barcus is also on Facebook.

Leave a comment