2001 Archives.

My archives, June 6, 2001, posting by coincidence w Philip Glass’ 85th birthday bash. Happy Birthday! My interview with Philip Glass just before his 2001 Spoleto performance of The Screens, a collaborative piece composed along with West African-born composer and griot, Foday Musa Suso. What an honor for me. My fellow-critic/friend, Robert T. Jones, then critic for Charleston Post and Courier, and editor for Glass’ “Music by Philip Glass”, hipped me to the composer (and fellow Marylander!). See for yourself in the interview, he’s a swell guy!

The world through glass eyes

Behind The Screens, the Wizard of Music

By S.E. Barcus, Charleston City Paper, June 6, 2001

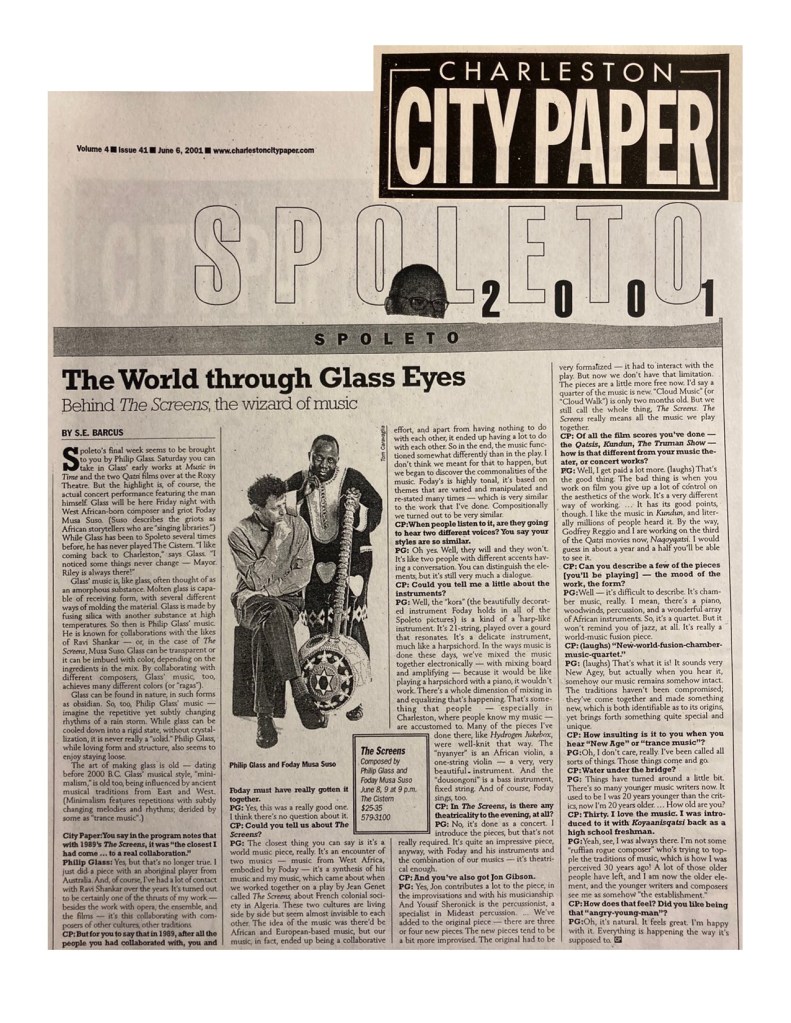

Spoleto’s final week seems to be brought to you by … Philip Glass. Saturday you can take in Glass’ early works at Music in Time and the two Qatsi films over at the Roxy Theatre. But the highlight is, of course, the actual concert performance featuring the man, himself, Glass will be here Friday night with West African-born composer and griot Foday Musa Suso (Suso describes the griots as African storytellers who are “singing libraries.”) While Glass has been to Spoleto several times before, he has never played The Cistern, “I like coming back to Charleston,” says Glass. “I noticed some things never change – Mayor Riley is always there!”

Glass’ music is, like glass, often thought of as an amorphous substance. Molten glass is capable of receiving form, with several different ways of molding the material. Glass is made by fusing silica with another substance at high temperatures. So then is Philip Glass’ music. He is known for collaborations with the likes of Ravi Shankar – or, in the case of The Screens, Musa Suso. Glass can be transparent or it can be imbued with color, depending on the ingredients in the mix. By collaborating with different composers, Glass’ music, too, achieves many different colors (or “ragas”).

Glass can be found in nature, in such forms as obsidian. So, too, Philip Glass’ music -imagine the repetitive yet subtly changing rhythms of a rain storm. While glass can be cooled down into a rigid state, without crystallization, it is never really a “solid.” Philip Glass, while loving form and structure, also seems to enjoy staying loose.

The art of making glass is old – dating before 2000 B.C. Glass’ musical style, “minimalism,” is old, too, being influenced by ancient musical traditions from East and West. (Minimalism features repetitions with subtly changing melodies and rhythms; derided by some as “trance music”.)

City Paper: You say in the program notes that with 1989’s The Screens, it was “the closest I had come … to a real collaboration.”

Philip Glass: Yes, but that’s no longer true. I just did a piece with an aboriginal player from Australia. And, of course, I’ve had a lot of contact with Ravi Shankar over the years. It’s turned out to be certainly one of the thrusts of my work -besides the work with opera, the ensemble, and the films – it’s this collaborating with composers of other cultures, other traditions.

CP: But for you to say that in 1989, after all the people you had collaborated with, you and Foday must have really gotten it together.

PG: Yes, this was a really good one. I think there’s no question about it.

CP: Could you tell us about The Screens?

PG: The closest thing you can say is it’s a world music piece, really. It’s an encounter of two musics – music from West Africa, embodied by Foday – it’s a synthesis of his music and my music, which came about when we worked together on a play by Jean Genet called The Screens, about French colonial society in Algeria. These two cultures are living side by side but seem almost invisible to each other. The idea of the music was there’d be African and European-based music, but our music, in fact, ended up being a collaborative effort, and apart from having nothing to do with each other, it ended up having a lot to with each other. So, in the end, the music functioned somewhat differently than in the play. I don’t think we meant for that to happen, but we began to discover the commonalities of the music. Foday’s is highly tonal, it’s based on themes that are varied and manipulated and restated many times – which is very similar to the work that I’ve done. Compositionally we turned out to be very similar.

CP: When people listen to it, are they going to hear two different voices? You say your styles are so similar.

PG: Oh, yes. Well, they will and they won’t. It’s like two people with different accents having a conversation. You can distinguish the elements, but it’s still very much a dialogue.

CP: Could you tell me a little about the instruments?

PG: Well, the “kora” (the beautifully decorated instrument Foday holds in all of the Spoleto pictures) is a kind of a harp-like instrument. It’s 21-string, played over a gourd that resonates. It’s a delicate instrument, much like a harpsichord. In the ways music is done these days, we’ve mixed the music together electronically – with mixing board and amplifying – because it would be like playing a harpsichord with a piano, it wouldn’t work. There’s a whole dimension of mixing in and equalizing that’s happening. That’s something that people – especially in Charleston, where people know my music – are accustomed to. Many of the pieces I’ve done there, like Hydrogen Jukebox, were well-knit that way. The “nyanyer” is an African violin, a one-string violin – a very, very beautiful instrument. And the “dousongoni” is a bass instrument, fixed string. And of course, Foday sings, too.

CP: In The Screens, is there any theatricality to the evening, at all?

PG: No, it’s done as a concert. I introduce the pieces, but that’s not really required. It’s quite an impressive piece, anyway, with Foday and his instruments and the combination of our musics – it’s theatrical enough.

CP: And you’ve also got Jon Gibson.

PG: Yes, Jon contributes a lot to the piece, in the improvisations and with his musicianship. And Yousif Sheronick is the percussionist, a specialist in Mideast percussion. … We’ve added to the original piece – there are three or four new pieces. The new pieces tend to be a bit more improvised. The original had to be very formalized. It had to interact with the play. But now we don’t have that limitation. The pieces are a little more free now. I’d say a quarter of the music is new. “Cloud Music” (or “Cloud Walk”) is only two months old. But we still call the whole thing, The Screens. The Screens really means all the music we play together.

CP: Of all the film scores you’ve done – the Qatsis, Kundun, The Truman Show – how is that different from your music for theater, or concert works?

PG: Well, I get paid a lot more. (laughs) That’s the good thing. The bad thing is when you work on film you give up a lot of control on the aesthetics of the work. It’s a very different way of working. … It has its good points, though. I like the music in Kundun, and literally millions of people heard it. By the way, Godfrey Reggio and I are working on the third of the Qatsi movies now, Naqoyqatsi. I would guess in about a year and a half you’ll be able to see it.

CP: Can you describe a few of the pieces [you’ll be playing] – the mood of the work, the form?

PG: Well – it’s difficult to describe. It’s chamber music, really. I mean, there’s a piano, woodwinds, percussion, and a wonderful array of African instruments. So, it’s a quartet. But it won’t remind you of jazz, at all. It’s really a world-music fusion piece.

CP: (laughs) “New-world-fusion-chamber-music-quartet.”

PG: (laughs) That’s what it is! It is! It sounds very New Agey, but actually when you hear it, somehow our music remains somehow intact. The traditions haven’t been compromised; they’ve come together and made something new, which is both identifiable as to its origins, yet brings forth something quite special and unique.

CP: How insulting is it to you when you hear “New Age” or “trance music”?

PG: Oh, I don’t care, really. I’ve been called all sorts of things. Those things come and go.

CP: Water under the bridge?

PG: Things have turned around a little bit. There’s so many younger music writers now. It used to be I was 20 years younger than the critics, now I’m 20 years older. … How old are you?

CP: Thirty. I love the music. I was introduced to it with Koyaanisqatsi as a high school freshman.

PG: Yeah, see, I was always there. I’m not some “ruffian rogue composer” who’s trying to topple the traditions of music, which is how I was perceived 30 years ago! A lot of those older people have left, and I am now the older element, and the younger writers and composers see me as somehow “the establishment.”

CP: How does that feel? Did you like being that “angry-young-man”?

PG: Oh, it’s natural. It feels great. I’m happy with it. Everything is happening the way it’s supposed to.

Featured image photo by Pasquale Maria Salerno, posted on Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/71349915@N00, posted on Wikipedia by Axel Boldt. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:AxelBoldt

Leave a comment