(A.k.a., A Contemporary Classical Feminist Ethnomusicological Documentary Symphony Masterpiece’s Northwest Premiere!)

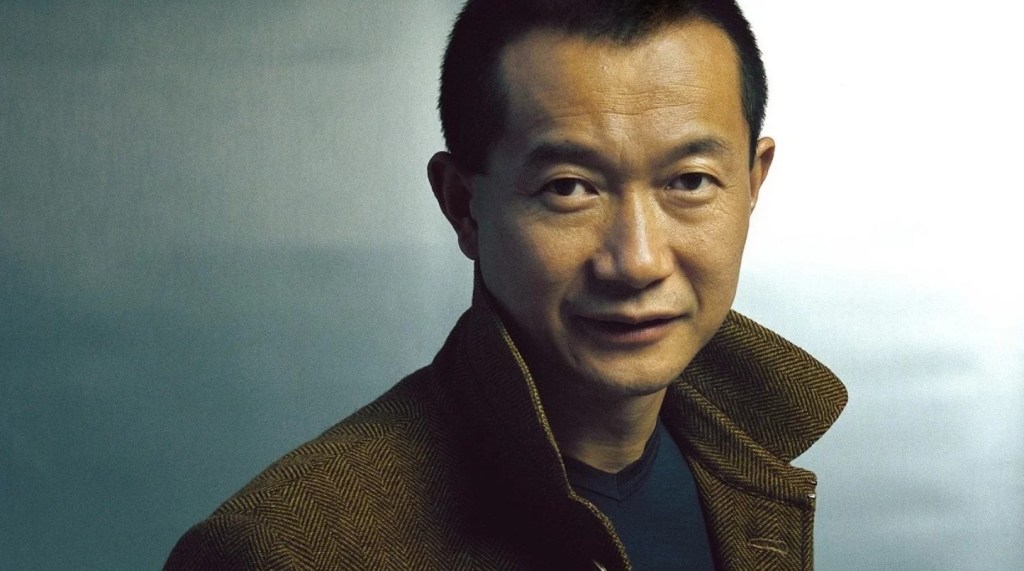

“Nu Shu: Secret Songs of Women,” performed by Seattle Symphony, Conducted by Tan Dun

Review By S.E. Barcus

Before this program tonight, I was indescribably excited. I’ve been waiting to hear Tan Dun live since the Seattle Symphony’s 2024-25 season schedule was announced. Academy-Award winning composer of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, coming to Seattle to conduct his own works, in person?!

I had read about him and the other Chinese composers that blossomed post-Cultural Revolution, in Alex Ross’ most-indispensable book on contemporary classical music, “The Rest Is Noise” – “their ignorance of tradition turned out to be a sort of bliss. … Tan, spent much of his childhood in a remote village in Hunan, singing folk songs while planting rice.” One day, when the loudspeakers blared Beethoven’s Fifth (performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra, touring China at the time) instead of proletariat propaganda, he knew at that moment that he wanted to compose music. He sold his father’s Korean war uniform for a 3-stringed fiddle, learned how to play, and after a tragedy befell the Peking Opera troupe, he was asked to play fiddle for them. … “When, at his entrance exam at the Central Conservatory in Beijing,” Ross writes, “he was told to play something by Mozart, he innocently asked, ‘who’s Mozart?’ (But) in the eighties, the Chinese ‘New Wave’ composers caught up fast, treading the progressive path from Debussy to Boulez to Cage. Yet they did not forget the rural musical traditions which they had been exposed while doing compulsory labor on collective farms.”

Tan Dun came to Columbia University, got his DMA, and has since then consistently been one of the most interesting composers alive today. (One wonders what he must think about the thought-policing by Trump against Columbia U, relative to his childhood experiences?) Has Tan Dun done an opera with an incredible premise, about Marco Polo?! Check. Composed music for Peter Sellars’ production of a condensed The Peony Pavillion opera? Check. Thrown traditional water and rock sounds into his scores, not in a chance-music or gimmick-y way like some (not all!) would argue was merry-prankster John Cage’s intent, but as a sincere, essential element to the music/sounds. Yup. Hey, this guy loves Paul Klee so much he friggin did a whole symphony about his art! Who is this crazy, interesting fellow?!

Why … Tan Dun, thank you. Here in Seattle, May 15 and 16, 2025, to conduct a program of Fire and Water pieces, culminating with the main event – his “Nu Shu: Secret Songs of Women.” Years ago, while in Taiwan on tour, Tan was reportedly ashamed that he had never heard about the recently ‘discovered’ secret language and songs of the women of Hunan – his original home. This secret written language was developed by women at least 700 years ago, and is MEANT to be sung or chanted. (What an amazing discovery for a contemporary composer — who himself reportedly loved the famed composer and ethnomusicologist, Bartók — to make! And with women from his home region, no less! The stories behind this work are as awe-inspiring as the piece, itself!)

Tan Dun lived amongst the surviving speakers/singers of this language for five years. Initially there were only 13 left alive, then only six after his five years with them. (I wonder if the 13 parts are in homage to these 13 women?) He made video and audio recordings, saving this language and these songs for posterity. He says it took a while for the women to come to trust him, understandably, given the very nature of these songs, but eventually (after he cooked them enough yummy meals!), it seems they bonded and befriended one another, and now we all have this work to thank for it! (While Tan says he is more an artist than anthropologist, the Chinese government reportedly did not do this important work on their own – and asked Tan for these important recordings. So, sorry Tan, you are a bona fide ethnomusicologist and preserver of knowledge, in my book!)

“Nu Shu,” in 13 parts, is performed with the videos he took. None of these women survive now – yet here they are for all of us. If you’re in Seattle, get to the show Friday! You have to experience this! Perfectly situated between Mother’s Day last weekend and the Chinese Cultural Festival at Seattle Center this weekend, the piece features accompanying videos that hang overhead, with original audio songs sung by the original, surviving women, perfectly calibrated with the live orchestra below them. This makes the experience so incredibly moving and meaningful. Tan Dun ultimately toured this work in China, about the women from Hunan, in 2014 with the Phily Orchestra — the same orchestra that awoke in him the desire to play music as a child back in Hunan.… One can’t even imagine how deeply moving that must have been for him. (Just a crazy story….)

Now, don’t be stupid like me and ask, “why do you think women had to have a secret language?” Um … duh. Why do we think? Every human civilization’s favorite pastime — Patriarchy! … They were forbidden an education, were not allowed to learn to read or write, so they invented their own language, with their own written syllabic version of it. Their lives were repressed, and they felt like, “useless branches” within patriarchal society. These were ways to pass down knowledge, experience, to endure, to commiserate, and to share stories with daughters and mothers and sisters for centuries, unbeknownst to any male until just the late 20th century. Which is just … mind-blowing. (Until some heard them chant it, and thought they were insane, or witches….)

The piece is typical for much of Tan Dun’s career, utilizing Western symphonic sounds and traditional Chinese songs and melodies and instruments. Here, the singing is all Chinese folk music, with much of the orchestra more tonal Western sounds, from a Gershwin-ish “American in Paris,” feeling of bounciness in the village and on the road, in parts 5 and 7 (complete with horns sliding by, like cars on a street), to Stravinsky-ish powerful neoclassical sounds, to even opening the whole thing with something slightly reminiscent of Ligeti’s Atmospheric “spider-webs” (until the harp gently creeps out with the main theme). Which makes it all a sort of pastiche-pomo-collage like a John Adams piece or something, then back to the traditional Chinese folk music. All effortless, and intentional, everything in its right place. Nothing about this work comes off as forced or insincere – indeed, it is one of the most moving and sincere pieces I’ve heard. Regarding the music, Tan Dun mentions that the melody is even more ancient than pentatonic – and is filled with tri-tones. But I don’t hear them so much? All of the songs – and the main melody within the orchestra, rising to a repeated crescendo at the end – are pentatonic, as far as I can tell. I rarely if ever heard that “Ma-RI-a” tri-tone, that 5th element of a diminished chord. (I will have to study the sheet music and try to find them!)

With all of these various styles seamlessly tied together, composition-wise, then, Tan Dun seems to have arrived at the working method of many of our current Western (and otherwise) composers – using “everything in the tool box” and foregoing the tribalistic “style wars” of the middle 20th century as silly and a waste of time. All music can be beautiful – if one is dedicated to making sure they put in the right style, the right note, the right rhythm, the right technique, that fits a given work. Period. Tan Dun – perhaps coming into New York so fresh, as Ross pointed out – might just be way ahead of the curve. The current “everything in the toolbox” zeitgeist is Tan Dun — and he’s been doing it for decades.

Part 4, is a wedding song, “Dressing for the Wedding,” the most moving piece of the night. Filled with tears and wails, it screams “arranged marriage” of a teenage girl (likely to some creepy old man). It is horrific and heart-breaking. For similar reasons, so is “Longing for her Sister” and “Soul Bridge,” all referencing the undoubtedly lonely and saddened life of women pulled apart from their own families. Often the singing of the women is itself bridged by the lone, powerful harp.

And what wonderful use of this harp! Besides typically lush rolling arpeggios from the harp, Tan Dun uses any of the “extended techniques” that he wants, if they fit. Harpist Xavier de Maistre was excellent throughout, at times playing the sweet and cinematic melodies, while at other times, strumming or slapping the harp like it’s a guitar. Tan Dun picked the harp because it is often considered the most “feminine,” for these songs of women – and feminine and strong and powerful it is, all night. During “Grandmother’s Echo,” there is a scraping down the string that matches any of the disturbing noise of Sonic Youth. And just to bend genders throughout the night, de Maistre is the first male harpist to play the piece, as far as I can tell, by named harpists of past performances.

Horns get louder and louder … and disturbingly louder, still … at the end of part 12, to wake you up for part 13, which might seem a little too celebratory to some, after such sad moments beforehand, with the women all singing together while washing clothes in the water – to the tune of now-familiar-to-us water sounds (from the earlier piece of the night, below), played by the orchestra. But in the big scheme of things, celebrating life, celebrating the endurance and inventiveness and perseverance of these women involved with this language over the centuries – yes, it is worth celebrating. These forgotten women are worth celebrating. The end sings that life is worth celebrating, triple forte.

To have video incorporated within the piece is wonderful. Seattle Symphony did that with Messiaen’s From the Canyons to the Stars last year, and I loved it. (Although some in the audience were laughably furious with that program last year. I overheard one member say, “how dare you put up images and try and tell ME how to think about music! I’ll think about it the way I want to, thank you very much!” Like, wow, what an opinionated fan!) Laurie Anderson does this all the time, of course. Steve Reich did it with Three Tales, which I didn’t like as much, given its anti-science-stance. And so, here, like those two, the videos are all PART of the work. The work cannot be said to have been performed WITHOUT the videos and their songs. So, while this is called a symphonic piece, or a “documentary symphony,” it’s really swinging closer to multimedia art, with contemporary classical music as the primary focus. And it’s wonderful – the blurring of lines of art and music and song and drama…. More of this will move the arts along and help them to thrive.

***

The rest of the program was a lot of fun. Manuel de Falla’s “Ritual Fire Dance,” was a great amalgam of Spanish themes – some Bolero-ish build-up here and there — set to a speedy tempo, given it was a frenetic dance, like Nora’s Tarantella, with strings flickering like flames. The video above showing fire, and the lights all red. Very nice. Short and sweet.

Then, balancing the fire — the coolness of the water, with the amazing “Water Concerto” (how could it not be amazing, being dedicated to Takemitsu?!). Our percussionist, Yuri Yamashita, opened the piece breaking the 4th wall, coming down through the audience aisle with some watery percussive instrument called the waterphone, that looks like a World Series trophy. Video showed her hands close up in the two drums of water, with their hands getting sounds of subtle drips or splashes, depending on maneuvering (the same techniques, of which, could be seen by Seattle Symphony’s percussionists in “Nu Shu”…). Extended techniques of the horns made them sound like kazoos, or even like silly haunted house winds.

Yamashita at times uses a cup to get a more poofy water sound, might bong a metal pan in the water to get a more chime-like water sound, all surrounded by the orchestra, with shaking rocks, and occasional pizzicato strings sounding like little rain drops, themselves. And then comes the mind-blowing water-drum solo. By the end of it, Neil Peart would bow down to Yamashita and her playing of Tan Dun’s piece. Listen closely to her foot stomp or mouth clink accompanying her assiduous splashing. (At one point, a little bossa nova could be made out…. What’s that she’s singing? … Ah! “Agua de beber,” of course!)

Tan Dun was mostly straightforward and no-nonsense in his conducting, standing straight, chopping the air with a broad arm at times. But near the end of the water concerto, with the waviness of the strings, he literally waved his body like a belly dancer to get the effect from our musicians. And he leaped up like an explosion to get those fireworks, during Stravinsky’s “Fireworks” piece. And caressed the air with his hands as the percussionists rubbed the rocks together to make sounds of a shushing windy breeze through leaves…. All just wonderful to have seen and experienced.

Tan Dun has called his Nu Shu a “soundscape monument for mothers, daughters, and sisters.” “Monument” is a good word choice. Despite all of the amazingly ambitious and wonderful music this composer has already made throughout his life, I can’t imagine anything will top this piece, along with all of the real, human mythology surrounding it, from the creation of the language to all of the work creating the art. It’s great music, complete with a great story. It rarely gets better than that in Art. It is like a song carved into one of Tan Dun’s signature rocks, up on a mountain, there for all to see and hear, for many, many generations of women, and men, to come. A monument.

Copyright 5-15-2025

Featured image a screen grab from NPR, with photo given courtesy of the artist.

Leave a comment